An urban hotspot: Eleonas camp, between migration and urban governance

Sossich Erasmo

Ethnic Groups, Housing, Quartiers

2025 | Sep

From the summer of 2015 until the fall of 2022, Eleonas camp[1] was one of the main Athenian reception facilities, embodying many of the transformations which have characterized the evolution of the governance of the “refugee issue” in Greece during the last decade. As such transformations concerned changes in the role of the central and local government, international organisations and civil society, it is argued that an analysis of the Eleonas camp trajectory, concluded in 2022 through a complex eviction and the “regeneration” of the site, shows a convergence of urban and migration governance, a convergence which appears to be a distinctive trait of the Greek “Multilevel Governance” of migration.

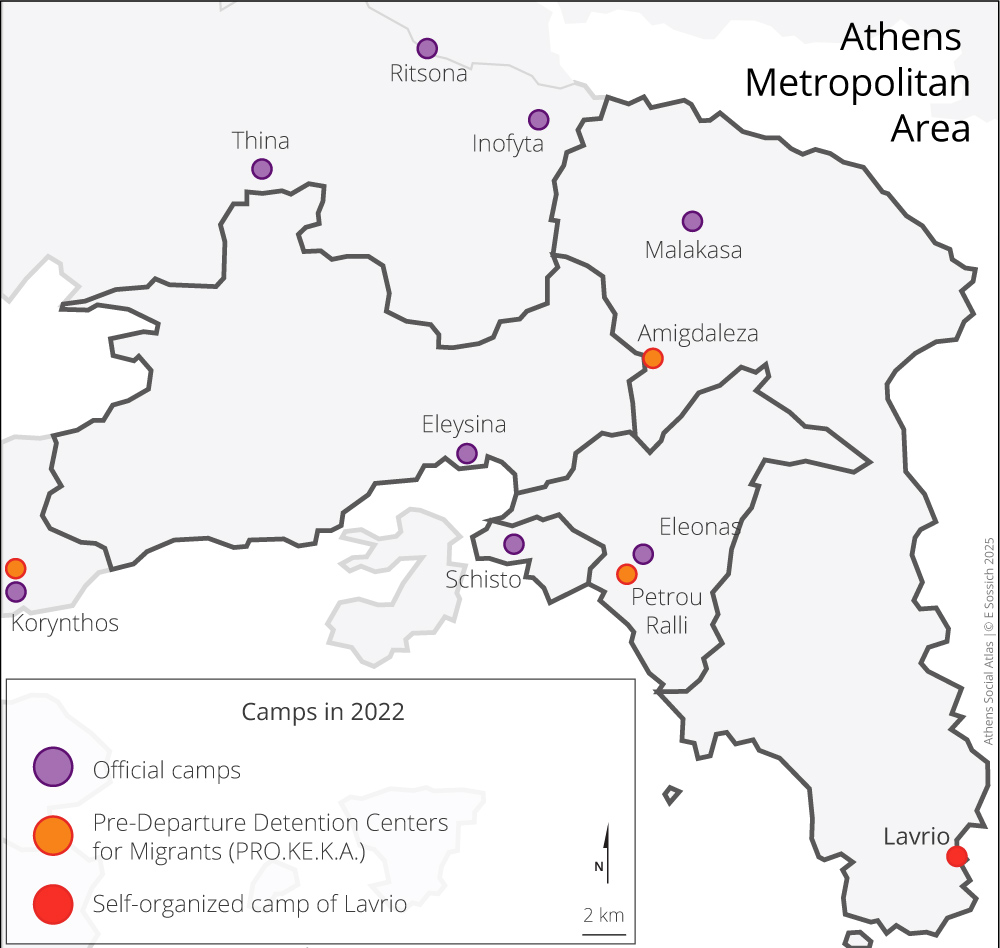

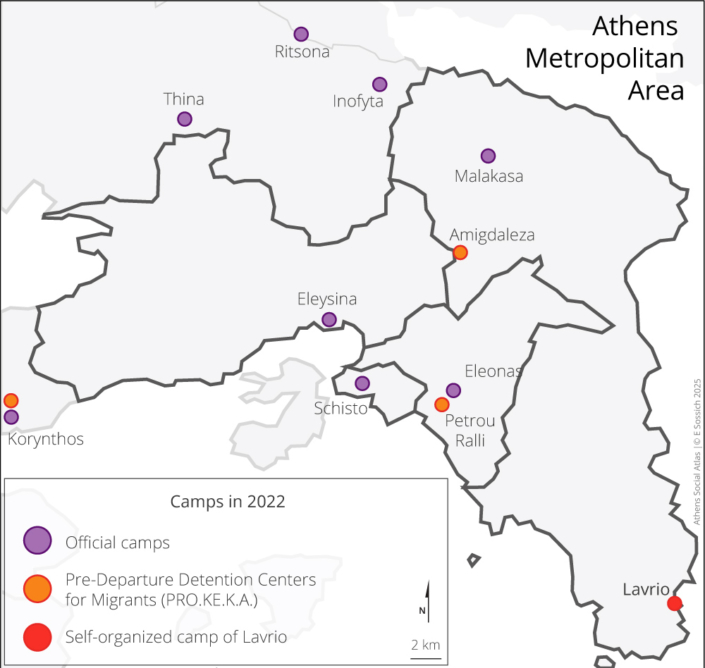

Χάρτης 1: Camps in 2022

Phase 0. The long summer and the creation of Eleonas camp

The so-called “refugee crisis” started with the arrival of over 800.000 migrants on the Greek shores by the end of the summer 2015 (UNHCR, 2024), and was soon followed by the closure and militarization of the borders along the Balkan route by March 2016 (Anastasiadou et al., 2017). As the Aegean islands and the main cities witnessed the passage of hundreds of thousands of people on the move and the presence of tens of thousands trapped by the closed borders, the Greek parliament was facing the failure of the national debt negotiations, the resignation of the first Tsipras government and the management of new elections. In the absence of a coherent reception policy, the “long summer of migration” was therefore characterized by the initiative of Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs), local and international NGOs, municipal actors, solidarity movements and, above all, the migrants themselves. In Athens, adding to dozens of informal encampments scattered around the city parks and squares, shelter was provided with via a set of emergency structures located in large facilities which could host large numbers of people, as the main building of the abandoned airport of Elliniko, three large Piraeus port warehouses and several post-olympic sports facilities. Nominally managed by institutional actors, but kept in function thanks to the efforts of their temporary inhabitants, NGOs and solidarians, these structures lacked a unified administration and, depending on each different facility, were classified either as “First-line”, “Second-line” or “temporary” reception (ECRE, 2016).

The exception was Eleonas camp: opened on the 16th of August of 2015 at the initiative of the first Tsipras government with the support of UNHCR, the camp was the first “official” reception structure to operate under the supervision of the First Reception Service [2]. The camp was managed by the General Secretariat of Migration Policy [3] and the Ministry of Interior and Administrative Reconstruction, and run by Mahmoud Abdelrasoul in the role of camp manager. Notably, Abdelrasoul had graduated in medicine, was 29 years old, had Sudanese origins and had become a Greek citizen in February of that same year. An important role was also played by the municipality of Athens, led by the center-left mayor Giorgos Kaminis, through the municipal company EATA, which provided both technical personnel and social workers. Other organizations active in the camp were the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, the Asylum Service, the army, the IOM, the UNHCR, MSF, and at least 4 local NGOs.

Situated on an abandoned municipal site and the only one close to the city centre, to which it was linked by several bus lines and a metro station, the structure was intended for the temporary reception of “vulnerable” subjects. Nevertheless, its location followed a tradition of containment and convergence of “unwanted” populations in disadvantaged areas (Cheshire & Zappia, 2015) as Eleonas, once a dynamic industrial area, had long been labelled an “urban void” [4]. By October the camp consisted of 90 housing containers for a capacity of 750 people (European Commission, 2015) [5], and by December it had hosted 9.725 people (Cupulo, 2015). By March 2016 it officially hosted 712 migrants, mostly Afghans and Iranians, while an extension of another 600 places was almost completed (IOM, 2016: 16).

Phase 1. The EU-Turkey Statement and the new governance

The EU-Turkey Statement, approved in March 2016 and implemented by the second Tsipras government through Law 4375/2016, marked a new course for the governance of migration. While keeping a mostly tolerant attitude toward squatting and other practices of “self-settlement”, the law recast the “First Reception Service” into the “Reception and Identification Service” (RIS), aiming at unifying and centralizing the administrative practice. Not only this law introduced the “geographical restrictions” and the “repatriation” to “safe” third countries, but it laid the foundation of the still existing camp system. The law defined a new type of refugee camps serving as hotspots in the Aegean island, the “RICs” (Reception and Identification Centers), while also establishing the system of mainland “reception structures” through which what I call the extra-urban confinement of migrants would be implemented, classified either as “Temporary Reception Facilities for Asylum Seekers” (Δομές Προσωρινής Υποδοχής Αιτούντων Διεθνή Προστασία), as was the case of Eleonas camp (HBA, 2017), or by the title “Open Temporary Accommodation Facilities” (Δομές Προσωρινής Φιλοξενίας) if destined to host persons subject to return procedures or whose return has been suspended. As these new and camp-liked structures opened, the residents of the “Phase 0” reception facilities were transferred there and by 2017, 5 hotspot camps, with a capacity of over 8.000 places and more than 30 mainland camps (8 of which were located nearby Athens), with a capacity of over 30.000 places, were operational (AIDA, 2017: 22, 98-99), even if by the same year arrivals had decreased to 36.310 (UNHCR, 2024). Except for the radical fringes of the solidarity movement, the actors who had promoted the reception initiatives during the “crisis” were included in a process of ‘top-down’ and ‘downward’ devolution (Guiraudon & Lahav, 2000), marking the beginning of a ‘Multilevel Governance’ (MLG) of migration in the Greek context [6].

The new “reception system” was characterized by the centrality of “international protection” and “vulnerability” (Spathopoulou et al., 2020; Glyniadaki, 2021), reflected in the complementarity of camps, in the great majority located far away and scarcely connected to urban centers, and urban accommodation programs reserved for “vulnerable” subjects, which had grown to a capacity of 27.000 places by 2018 (UNHCR, 2021). Pivotal roles were played by the IOM, by the UNHCR and by the municipalities, the first as “Site Management Support” (SMS) in most camps, the others as promoters of “humanitarian” projects and accommodation programs (Stratigaki, 2022), mostly grouped by the UNHCR into the ESTIA programme by 2017, while the actual provision of housing and any other kind of “humanitarian” aid passed through the ubiquitous employment of local and international NGOs.

Following the “Statement”, Eleonas camp had been made permanent and had reached a capacity of 2.500 places, with 205 housing containers hosting 2.183 “vulnerable” residents, in majority women and children of Afghan and Syrian nationality (UNHCR, 2016). By 2018, the camp had grown to accommodate 297 housing containers (UNHCR, 2018) and a new manager, Dimitris Georgiadis, had been appointed. Coming from a research career in social sciences (Georgiadis, 2023), Georgiadis had worked as a Career Counselor in a Second Chance School and in a Mental Health Center. As the camp functioned thanks to a large assemblage of humanitarian actors, including new international NGOs, it also grew in popularity, being visited by numerous public personalities, such as the former French president Hollande, and hosting intercultural events (Ministry of Education, 2018).

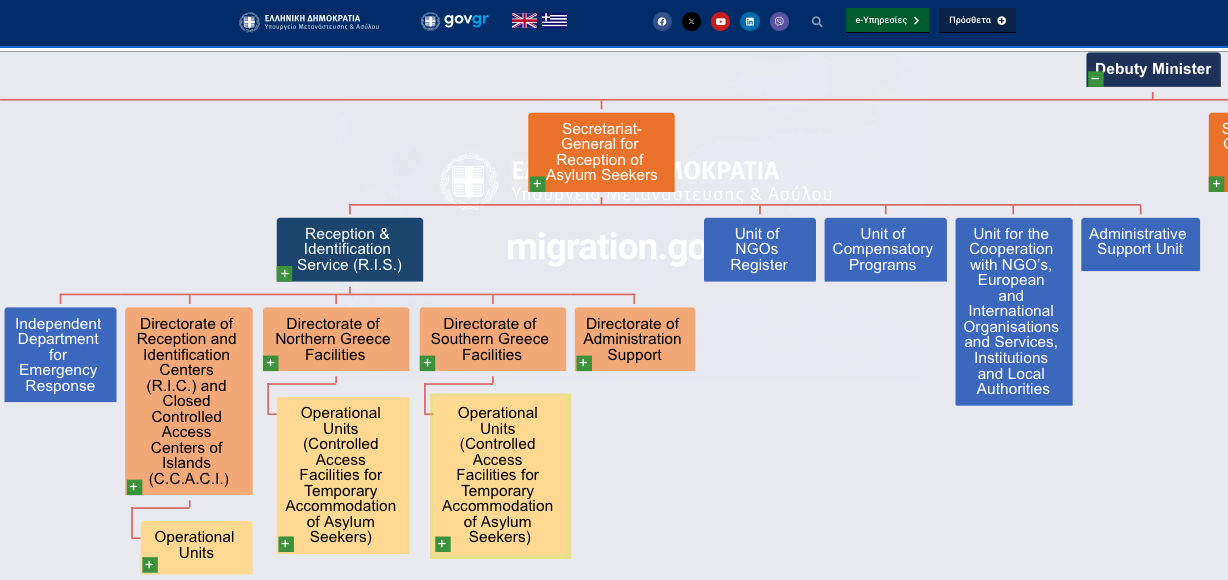

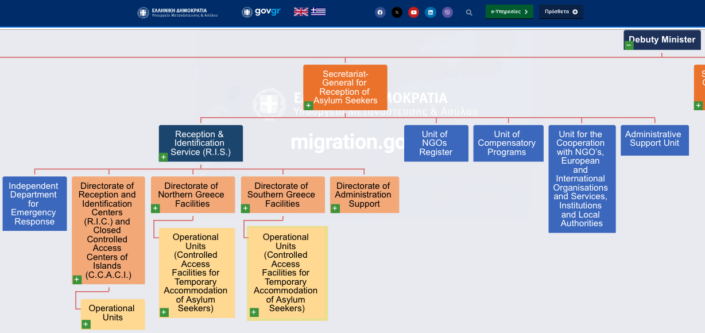

Phase 2. The consolidation of the camps’ system

New Democracy’s victory in 2019 national and municipal elections, followed by the appointing of Kyriakos Mitsotakis as Prime Minister and his nephew Kostas Bakoyannis as mayor of Athens, marked the beginning of a second phase. With regard to external bordering, from 2020 on a systematic recourse to push-backs was documented, making border crossing more dangerous. With regards to the “reception system”, the government passed several pieces of legislation[7]

through which it created the Ministry of Migration and Asylum (MoMA), changed once more the classifications of the various structures and, most notably, put them under the supervision of ministerial appointed camp directors, centralizing many tasks previously assumed by the IOM and UNHCR (AIDA, 2021). The structures were reorganized as:

- 5 CCACs (Closed Controlled Access Centers) – ΚΕΔ (Κλειστές Ελεγχόμενες Δομές) working as island hotspot camp

- 3 RICs (Reception and Identification Centers) – ΚΥΤ (Κέντρα Υποδοχής και Ταυτοποίησης) in specific strategic locations

- 24 CAFTAAS (Controlled Access Facility for Temporary Accommodation of Asylum Seekers) – ΕΔΠΦΑΑ (Ελεγχόμενες Δομές Προσωρινής Φιλοξενίας αιτούντων άσυλο) mainland camps [8]

Figure 1: Organizational chart of the Ministry of Immigration and Asylum

Source: ΥΜΑ, 2023

Adding to these are 7 PRDCs, also known as PROKEKA (Pre-Removal Detention Centers), even though such structures were never part of the “reception system”(AIDA, 2024: 226). Moreover, it introduced the “NGO registry” (Amnesty International, 2020), limiting the number and the autonomy of NGOs in the camps, and restricted the access to the camps to their staff and residents, allegedly in response to the pandemic of Covid-19. As these restrictions became permanent, fences and gates were erected around the structures. Furthermore, in 2020 the government took over the ESTIA program and soon announced its closure by February 2022, marking a fundamental change from a reception policy based on the complementarity of housing schemes for vulnerable subjects and refugee camps to a system consisting solely of camps.

Accordingly, in Athens both the national and the municipal institutions and agencies explicitly pursued an agenda aimed at reducing the migrants’ presence. As a first step, in 2019 the police evicted dozens of squats, transferring most of their residents into the mainland camps. As a second step, the government planned the construction of bigger island “reception structures”: nevertheless, the project backfired as islanders rioted, leading the MoMA to initiate the so-called “island decongestion strategy”. Alas, the “decongestion” was mostly carried out informally, reducing police surveillance on the “geographical restrictions”, and many of those who arrived in Athens found shelter in self-built encampments. As the authorities relocated hundreds of migrants in Eleonas camp many others followed, inhabiting in self-built shacks and tents or sub-renting places inside the housing containers, while hoping to be re-registered in the “reception system”. More than ever, between 2020 and 2021 the camp functioned as an informal and negotiated, urban hot-spot, selecting, containing and channeling the migrants’ presence in the city. The occupancy rate rose from 87,4% in May (IOM, 2020a) to 102% in June (IOM, 2020b), stabilizing above 130% in August 2020 (IOM, 2020c). Still in December 2021 many lived in tents and the occupancy rate was at 109%, with 2.023 residents, of which only 763 were registered (IOM, 2021). While women and children were still a majority, most of the residents were now coming from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Afghanistan. Finally, by 2022 the island “decongestion” was over, and the government focused on its original goal: during the last months the last beneficiaries of ESTIA, around 12.500 “vulnerable” subjects, were either transferred to camps or evicted (RSA, 2022), and Eleonas camp faced its evacuation.

Double regeneration and double displacement

In November 2020, an agreement between the government, the municipality, Panathinaikos FC and a consortium of Alpha Bank and Piraeus Bank announced the return of the “Double Regeneration Project”, an operation aimed at building the new PAO stadium in Eleonas while creating a park on the site of the old one, along the central Alexandras avenue. The project, whose worth has been estimated around 500 million euros between public and private investments (Michas, 2022), followed the homonymous project approved in 2006 by the center-right administration of Dora Bakoyanni, the mother of Athens major Kostas Bakoyanni. Halted in 2013 due to the failure of a private investor, in 2007 the project had led to the eviction of a Roma camp, one in a series of displacements suffered by the Roma minority in the period of preparation for the Olympic Games and their aftermath (COHRE, 2007). After Bakoyanni’s decision, in October 2021, not to renew the MoMA concession of the site, by June 2022 the ministry started the mass relocation of the residents.

Figure 2: Memos distributed to residents by MoMA staff on the morning of the 16th of August

Source: E. Sossich 2022

Figure 3: Eleonas camp in June 2022

Source: E. Sossich, 2022

The evacuation was met by the unexpected mobilization of its inhabitants, led by tireless Congolese women and other representatives of the different groups inhabiting the camp. After a week-long sit-in in front of the camp gates had stopped the first mass-relocation attempts, the residents organized several demonstrations and, claiming that a relocation to the mainland camps would involve the deterioration of their living conditions as well as the loss of any chance at integration for their children, met the municipal council and MoMA representatives. Undeterred, by the beginning of July the authorities interrupted all projects taking place in the camp, halting the activities of the IOM, EATA and several NGOs, and appointed a new camp manager, Maria-Dimitra Nioutsikou, who had already been the director of Samos island camp between 2016 and 2020[9].

After multiple police operations, the arrest of several solidarians and observers and more failed attempts at mass transfers, by September the previous camp manager was brought back and coupled to the new one. Eventually, the evacuation was carried out using small transfers and secrecy until the mobilisation lost its momentum. Without further opposition, a number of mass transfers was carried out, until the police evicted the last inhabitants on 30 November, and on December 12 the MoMA and the municipality signed the “Handover” of the area. A ceremony was organized in the camp, where the Prime Minister, the Minister of Immigration and Asylum, and the mayor of Athens celebrated the beginning of the project, the “success of the management of the migration problem”, the “decongestion of Athens”, the “return of this part of the city to the citizenship” (Prime Minister GR, 2022). Following the “successful evacuation” of the camp, Nioutsikou was appointed Deputy Governor of the RIS, the governing body of the Greek “reception” system (MoMA, 2024).

Figure 4: Prime Minister Mitsotakis during his speech in Eleonas

Source: Iefimerida (2022). Mitsotakis on Eleonas: It is not just a double reconstruction, but a double and timely response. (Μητσοτάκης για Ελαιώνα: Δεν πρόκειται απλώς για μια διπλή ανάπλαση, αλλά για μια διπλή και επίκαιρη απάντηση). 12.12.2022

A multilevel convergence of migration and urban governance

The case of Eleonas camp shows how a “Multilevel Governance of Migration” can prompt the dual convergence of migration and urban governance, and international and urban displacement (Roast et al., 2022), as the latter emerges as an instrument to dominate the “urban” ‘battleground of migration’ (Dimitriadis et al., 2021) while legitimizing new processes of capital accumulation. Many of the policies which shaped the MLG of migration appear to have been developed in order to channel or contain the presence of asylum seekers and refugees inside or outside the city, blurring the distinction between “migratory” and “urban” policies to the point where it could even be argued that migration policies have been transformed into urban ones. Such a dynamic could be explained by looking at two factors: the absolute centrality of Athens in the wider national political arena, and the succession of “center-left” and “center-right” administrators on both the municipal and national level, ensuring a degree of coherence in the implementation of national and local policies. Such circumstances avoided the insurgency of ‘decoupling patterns’, as is common in the case of local administrations who pursue agendas in opposition with the regional or national administration (Vergou et al., 2021).

Figure 5: Modern and ancient ruins. In the picture, taken in November 2024, the site where Eleonas camp was situated. The housing containers have been removed, but the construction works have not yet started.

Source: E. Sossich

However, the effectiveness of such policies in limiting the presence of asylum seekers in the city of Athens remains highly questionable. On the contrary, I believe that such policies have pushed more and more asylum seekers to find informal housing solutions, intensifying ethno-racial segregation in some areas of the city and segments of the rental market. Furthermore, the configuration of the “reception system” as a system of extra-urban confinement camps cannot simply be observed and highlighted, but must be openly rejected. Exiling the asylum seekers, denying their “right to the city”, limiting their individual and collective agency, increasing their isolation from civil society and their dependence on “humanitarian aid”, is pushing the exclusion of the asylants from “formal” citizenship to any form of “substantive citizenship” (Ambrosini & Hajer, 2023), jeopardising the universal enjoyment of rights which was set as a cornerstone of democracy, on the ashes of a continent dotted with camps.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Lamprini G. for the translation

[1] The camp’s first official name was “Open Accommodation Structure”, following JMD 3/5262, ‘Establishment of the Open Facility for the hospitality of asylum seekers and persons belonging to vulnerable groups in Elaionas Attica Region’, 18 September 2015, Gov. Gazette B2065/18.09.2015.

[2] The First Reception Service, established in 2011, would become the so-called “Reception and Identification Service”, or RIS, by April 2016.

[3] The Secretariat General of Migration Policy was part of the structure of the Ministry of the Interior. By 2016 it would be placed under the Ministry for Migration Policy.

[4] It is no mere coincidence that Eleonas already hosted Petrou Ralli’s Athens Immigration Police Office, (Διεύθυνση Αλλοδαπών και Μετανάστευσης Κεντρικού Τομέα και Δυτικής Αττικής Πέτρου Ράλλη – Directorate of Foreigners and Immigration of the Central Sector and Western Attica on Petrou Ralli, but simply called “Allodapon” by all immigrants) headquarter of the offices running the administrative procedures of renewal of foreigners residence permits but also used as a detention center for hundreds of undocumented immigrants.

[5] The numbers of residents counted by the IOM and other SMS were usually far exceeded by the actual number of unregistered residents who were informally hosted or sub-renting a place in the camp and, for a variety of reasons, adopted a wide set of strategies to invisibilize their presence.

[6] The category of “MLG of migration” identifies a governance model characterized by the coordination between various levels of government, IGOs, NGOs and other civil society actors, and it is often developed with the aim of being more adaptable than centralised or localised models (Dimitriadis et al., 2021).

[7] On 1 January 2020, the Greek International Protection Act (IPA), Greece’s fifth legislative asylum reform since the “Statement”, came into effect, although several adjustments to the law were not made until September 2021. Later on, in June 2022, L. 4939/2022 was adopted by the parliament, codifying several amendments introduced after 2019 in one piece of legislation, and finally a new migration code came into effect in Greece on 1 January 2024.

[8] In the last 5 years mainland camps have been referred to as:

– CTRC (Controlled Reception Centres for asylum seekers): αγγλική συντομογραφία που χρησιμοποιήθηκε από τη ΜΚΟ RSA και σύντομα υιοθετήθηκε από άλλους φορείς της κοινωνίας των πολιτών ως μετάφραση των «Δομών Φιλοξενίας Αιτούντων Άσυλο», μετά τη νέα ονοματοδότησή τους σύμφωνα με τα άρθρα 35 και 36 του Π.Δ. 106 – ΦΕΚ Α’ 255/23.12.2020. (RSA, 2024).

– CTAC (Controlled Temporary Accommodation Centres): αγγλικό αρκτικόλεξο που χρησιμοποιείται από τη ΜΚΟ AIDA και άλλους φορείς της κοινωνίας των πολιτών ως μετάφραση του ελληνικού τίτλου Ελεγχόμενες Δομές Προσωρινής Φιλοξενίας αιτούντων άσυλο (ΕΔΠΦΑΑ), κατηγορίας που ορίστηκε με το άρθρο 28 του Ν. 4825/2021 (προς τροποποίηση του Ν. 4375/2016).

– CAFTAAS (Controlled Access Facility for Temporary Accommodation of Asylum Seekers): αρκτικόλεξο που αποτελεί την επίσημη μετάφραση του ελληνικού τίτλου Ελεγχόμενες Δομές Προσωρινής Φιλοξενίας αιτούντων άσυλο (ΕΔΠΦΑΑ), κατηγορίας που ορίστηκε με το άρθρο 28 του Ν. 4825/2021. Το ΥΜΑ χρησιμοποιεί αυτά τα ακρωνύμια για να αναφερθεί στις ηπειρωτικές δομές, ενώ η διοίκηση του συστήματος υποδοχής είναι οργανωμένη στη βάση αυτής της κατηγοριοποίησης.

[9] In this period several NGOs voiced alarms on camps overcrowding and human right violations inside Samos camp, alarms which later led to several decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (I have rights, 2024; ECtHR, 2024).

Entry citation

Sossich E. (2025) An urban hotspot: Eleonas camp, between migration and urban governance, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/eleonas-camp/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.127

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

References

- Ambrosini, M., Hajer, M.H.J. (2023). “Agency, Inclusion and Political Mobilisation of Irregular Migrants”. Στο Irregular Migration. Springer, Cham.

- Amnesty International. (2020). Greece: regulation of NGOs working on migration and asylum threatens civic space. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 15.09.23.https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/EUR2528212020ENGLISH.pdf

- Anastasiadou, M., Marvakis, A., Mezidou, P., Speer, M. (2017). From Transit Hub to Dead End. A Chronicle of Idomeni. Munich: bordermonitoring.eu e.V.

- AIDA (Asylum Information Database). (2017). Country report: Greece. 2016 Update. https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/report-download_aida_gr_2016update.pdf

- AIDA (Asylum Information Database). (2021). Country report: Greece. 2020 Update.

https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/AIDA-GR_2020update.pdf - AIDA (Asylum Information Database). (2024). Country report: Greece. 2023 Update.

https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/AIDA-GR_2023-Update.pdf - Cheshire, L., & Zappia, G. (2015). Destination dumping ground: The convergence of “unwanted” populations in disadvantaged city areas. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2081–2098.

- COHRE, Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions. (2007). The Housing Impact of The 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. Σύνταξη: Theodoros Alexandridis, Greek Helsinki Monitor. http://www.ruig-gian.org/ressources/Athens_background_paper.pdf. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 19/10/24.

- Cupulo, D. (2015). Refugee relocation in Athens, 08/12/2015. DW.

https://www.dw.com/en/refugee-relocation-in-athens-hits-snags/a-18901144 - Dimitriadis, I., Hajer, M., Fontanari, E., Ambrosini, M. (2021). Local “Battlegrounds”. Relocating Multi-Level and Multi-Actor Governance of Immigration. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales. 37.

- ECRE. European Council on Refugees and Exiles. (2016). ECRE Comments on the European Commission Recommendation relating to the reinstatement of Dublin transfers to Greece – C(2016) 871.

https://ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ECRE-Comments_RecDublinGreece.pdf - ECtHR. (2024). Case of T.A. and others v. Greece. (Applications nos. 15293/20 and 3 others – see appended list). https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-236050.

- European Commission. (2015). Greece: Assessing the refugee crisis from the first country of reception perspective, 12 October 2015.

https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/news/greece-assessing-refugee-crisis-first-country-reception-perspective_en. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 18/09/2024 - Georgiadis, D. (2023). Human Rights, Racism and Migration: A philosophical approach. Interdisciplinary Research in Counseling, Ethics and Philosophy. 3/2023, 8: 121-135.

- Glyniadaki, K. (2021). Mixed Services and Mediated Deservingness: Access to Housing for Migrants in Greece. Social Policy and Society. 20(3): 464-474.

- Guiraudon, V., Lahav, G. (2000). A Reappraisal of the State Sovereignty Debate: The Case of Migration Control. Comparative Political Studies, 33(2), 163–195.

- HBA. (2017). ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ ΤΗΣ ΚΥΒΕΡΝΗΣΕΩΣ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΔΗΜΟΚΡΑΤΙΑΣ

https://www.hba.gr/UplFiles/fek/FEKB1940-17.pdf - I have rights. (2024). Το ΕΔΔΑ καταδικάζει την Ελλάδα για παραβιάσεις ανθρωπίνων δικαιωμάτων κατά επτά ασυνόδευτων παιδιών.

https://ihaverights.eu/ecthr-condemns-greece-for-human-rights-violations-against-seven-unaccompanied-children/. - IOM. (2016). Compilation of available data and information, March 2016. https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/Weekly%20Flows%20Compilation%20No11%2024March%202016%20Final.pdf. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 18/09/2024.

- IOM. (2020a). Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS) Factsheet May 2020. https://greece.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1086/files/documents/__5Merged%20Factsheet%20May_20.pdf

- IOM. (2020b). Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS) Factsheet June 2020.

https://greece.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1086/files/documents/__6Merged%20Factsheet%20June_20.pdf - IOM. (2020c). Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS) Factsheet August 2020.

https://greece.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1086/files/documents/__8Merged%20Factsheet%20Aug_20.pdf - IOM. (2021). Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS) Factsheet December 2021. https://greece.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1086/files/documents/_merged-mainland-december_21_compressed.pdf

- IOM. (2025). SMS FACTSHEETS. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 20/09/2025.

https://greece.iom.int/sms-factsheets. - Prime Minister GR. (2022). Ενημερωτικό σημείωμα για την παρουσία του Πρωθυπουργού Κυριάκου Μητσοτάκη στην τελετή παράδοσης – παραλαβής της Δομής του Ελαιώνα στον Δήμο Αθηναίων. 12 Δεκεμβρίου 2022. https://www.primeminister.gr/2022/12/12/30842.

- RSA, Refugee Support Aegean (2022). Σχετικά με τον τερματισμό του προγράμματος στέγασης ESTIA II για τους αιτούντες άσυλο.

https://rsaegean.org/el/gia-ton-termatismo-tou-estia-ii-gia-tous-aitountes-asylo/. - Spathopoulou, A., Carastathis, A., Tsilimpounidi, M. (2020): ‘Vulnerable Refugees’ and ‘Voluntary Deportations’: Performing the Hotspot, Embodying Its Violence. Geopolitics: 27(4), 1257–1283.

- Stratigaki, M. (2022). “A ‘Wicked Problem’ for the Municipality of Athens. The ‘Refugee Crisis’ from an Insider’s Perspective”. In: Kousis, M., Chatzidaki, A., Kafetsios, K. (eds) Challenging Mobilities in and to the EU during Times of Crises. Springer, Cham.

- UNHCR. (2016d). Site profiles – Greece – September 2016. Operational Portal Refugee Situation, Site Management Support. https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/52239. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 18/09/2024.

- UNHCR. (2018b). Site profiles August – October 2018. Operational Portal Refugee Situation, Site Management Support. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/66038. Τελευταία πρόσβαση 18/09/2024.

- UNHCR. (2021). ESTIA. A home away from home.

https://reliefweb.int/attachments/668b84c2-f2c3-309d-a754-4f6b47201b54/ESTIA%20programme-%20A%20HOME%20AWAY%20FROM%20HOME.pdf - UNHCR (2024). UNCHR, Operational Portal, Mediterranean Situation: Greece, διαθέσιμο στο: https://bit.ly/3WubNsb . Τελευταία πρόσβαση 31/10/2024.

- Vergou, P., Arvanitidis, P. A., Manetos, P. (2021). Refugee Mobilities and Institutional Changes: Local Housing Policies and Segregation Processes in Greek Cities. Urban Planning: 6.2: 19–31.

- Μίχας, Γ. Κλείνει η «μαύρη τρύπα» της Αθήνας. Liberal. 22-10-2022. https://www.liberal.gr/oikonomia/kleinei-i-mayri-trypa-tis-athinas.

- ΥΜΑ – Υπουργείο Μετανάστευσης και Ασύλου. (2023). Οργανόγραμμα Υπουργείου Μετανάστευσης & Ασύλου. https://migration.gov.gr/to-ypoyrgeio/organization-chart/

- ΥΜΑ – Υπουργείο Μετανάστευσης και Ασύλου. (2024). Διοίκηση & Επικοινωνία. https://migration.gov.gr/ris/organogramma-ypyt/.

- ΥΜΑ – Υπουργείο Μετανάστευσης και Ασύλου. (2025). Επιχειρησιακές μονάδες. https://migration.gov.gr/en/ris/perifereiakes-monades/

- Υπουργείο Παιδείας. (2018). 21-05-18 Την Κυριακή γιορτάσαμε ΜΑΖΙ στον Ελαιώνα – Μια μεγάλη γιορτή στην Ανοιχτή Δομή Φιλοξενίας Προσφύγων Ελαιώνα.

https://www.minedu.gov.gr/prosf-ekpaideusi-m/34737-21-05-18-tin-kyriakin-giortasame-mazi-ston-elaiona-mia-megali-giorti-stin-anoixti-domi-filoksenias-prosfygon-elaiona-3