Current state of building stock in the refugee settlements of the Central and Southern Sector of Athens

Toussi Evgenia

Built Environment, Planning, Quartiers

2024 | Sep

The Athens Central and Southern Sector comprises a multitude of refugee areas of varying scale, with buildings following different architectural standards. This investigation focuses on the current state of the building stock, outlining the quality of maintenance, land values and existing uses, while giving information on how these areas were originally designed. A comparative assessment of the evolution of different architectural options and their footprint in today’s city is carried out. The aim of the paper is to re-emphasize the issue of the refugee housing complexes, highlighting the variety of architectural choices and the multitude of scattered neighborhoods, mapping critical enclaves that face significant decay and abandonment.

The entry includes a bibliographic review, archival material study and field research, which took place between October and December 2023. The field research was carried out in the context of the Study Abroad Program, College Year in Athens, and the course “Social Housing and Social Exclusion. International Experience and the case of Athens”, lecturer E. Toussi with the participation of the following Undergraduate students: Cavanaugh Anissa (University of Notre Dame), Conte Isabella Kathleen – (Union College), Erickson Alyssa (University of Puget Sound), Hill Jordan Elizabeth (University of Notre Dame), Hochman Anna Gabrielle (University of Pennsylvania), Iannios Mia (The George Washington University), McCracken Fiona Rory (Furman University), Schwab Joseph (University of Puget Sound) and Skylar Yarter (Williams College).

Introduction

The city of Athens has a long history of about 3,400 years, making it both the capital and the largest city in Greece. Its formation and evolution are associated with demographic flows, historical conjunctures and socio-political transformations, shaping a socio-spatial palimpsest (Παπαευαγγέλου-Γκενάκου, 2023:12). Since 1830-1840, population inflows of different cultural origins, intensified after the end of the Balkan wars has been documented (Γκιζελή, 1984:88). However, the most important demographic flow is undoubtedly the refugee settlement of 1922, which was at its time the largest population relocation in the world (The National Geographic Magazine, 1925). In the international academic discourse, the study of refugee populations has been inaugurated as a separate scientific field since 1982 [1]. being characterized by its interdisciplinary nature. As scholars argue, refugee facilities have functioned, internationally, as an ideal field of experimentation, contributing to the implementation of social policy programs (Chimni, 2009).

The analysis of the contemporary urban fabric of Athens reveals significant socio-spatial influences from the refugee settlement of 1922, making this issue important for the interpretation of the Greek urban scenery (Τούση, 2014:12). Refugee housing, urban planning and street naming are just some of the elements of tangible heritage that facilitate the preservation of urban collective memory. In many cases, the severe damages on the refugee housing stock, in the wake of their housing rehabilitation, reminds us, that the study of refugee neighborhoods is not something that concerns the city of yesterday. It’s definitely something that concerns the city of today.

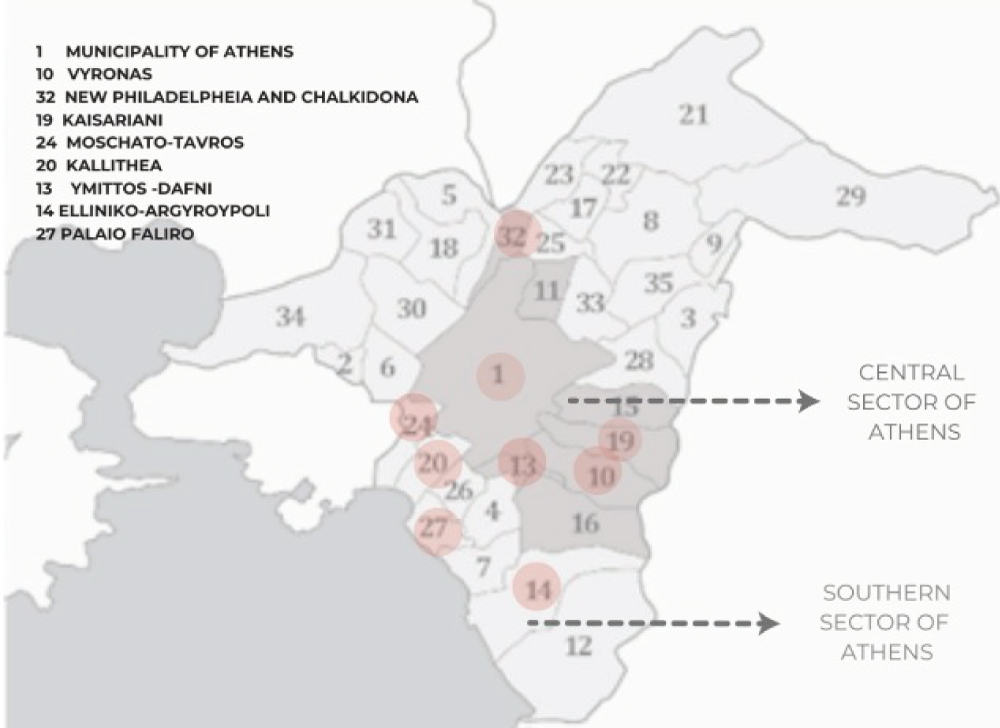

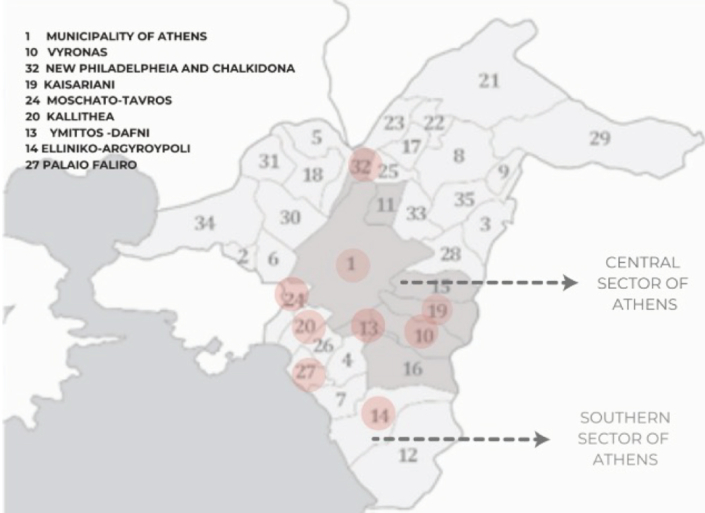

In view of this thesis, this article attempts to provide systematic information about the refugee settlements of the Central and South Athens Sector (figure 1), through a study of relevant literature, archival material and extensive field work, which includes field observation, building blueprints and semi-structured interviews with residents. This research attempts to connect the initial design to the current situation of the former refugee neighborhoods and draw conclusions on the effectiveness of the types of the refugee housing rehabilitation. Moreover, demolished refugee settlements in the area of study have been documented as an effort to preserve collective memory. This study paves the way for future research in the area, in terms of a micro-geographical approach, facilitating the study of specificities of time and place.

Figure 1: Administrative boundaries of the Central and Southern Sectors of Athens, marking in red the municipalities where Asia Minor refugees settled

Source: https://el.wikipedia.org and edition by the authors

The Initial Planning Process

After the Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922, more than 1,200,000 refugees [2] found shelter in Greece, overturning existing spatial and social equilibria (Χίρσον, 2004:11). In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne imposed the mandatory exchange of Greek and Turkish populations, the first in history (Χιρσον, 2004:11), shaping the general framework of resettlement (Clark, 2009:127). The Article 142 provided for mandatory population exchange, excluding the Greeks of Constantinople, Imbros, and Tenedos, as well as the Muslims of Western Thrace. The convention specified the persons to be exchanged, their nationality and their properties (Ελληνική Στατιστική Αρχή, 2022:12). Under the pressure of historical circumstances, many regions of the country associated their development with the refugee rehabilitation, in urban and rural areas (Βεϊνόγλου Μ και Φ., 1997:21).

In the field of urban rehabilitation, emphasis was placed on securing affordable housing (Ανδριώτης, 2020:144). Concerning the refugee housing rehabilitation, public bodies and organizations such as the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Refugee Fund (HCR), the Refugee Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) and the National Bank of Greece (NBG) were employed. The rehabilitation of refugees also involved private organizations as well as foreign charitable organizations such as the American and Swedish Red Cross, American Near East Relief and others (Τζεδόπουλος, 2007:74). In the wider area of the agglomeration Athens-Piraeus, 12 large and 34 small refugee settlements (Σαρηγάννης, 2000:105), were created, which until today, reflect their refugee past. In particular, in the area of today’s Central and Southern Athens Sector (figure 1) a number of different types of permanent refugee facilities had been recorded until 1959 (figures 1 & 2).

Figure 2: Permanent Refugee Settlements of the Capital Region, Ministry of Welfare, 1959

Source: The coding of the settlements is based on archival material from a relevant table by the Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region. Study of archival material, coding, and table design by E. Tousi, 2024

Figure 3: Cooperatives, Permanent Refugee Settlements of the Former Capital Region, Ministry of Welfare, 1959

Source: The coding of the settlements is based on archival material from a relevant table by the Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region. Study of archival material, coding, and table design by E. Tousi, 2024.

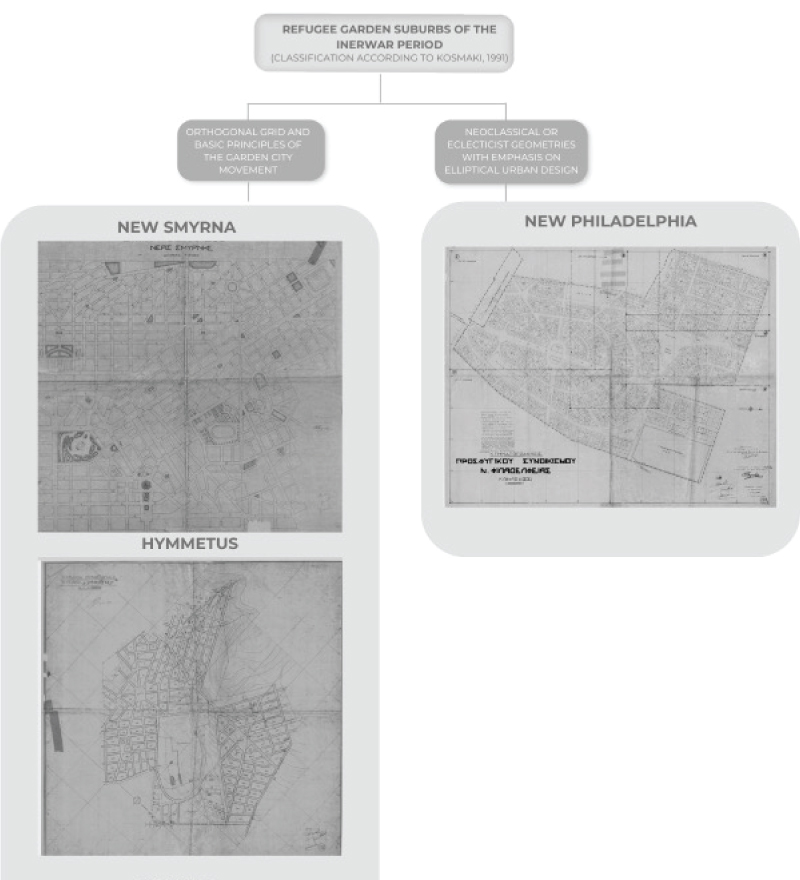

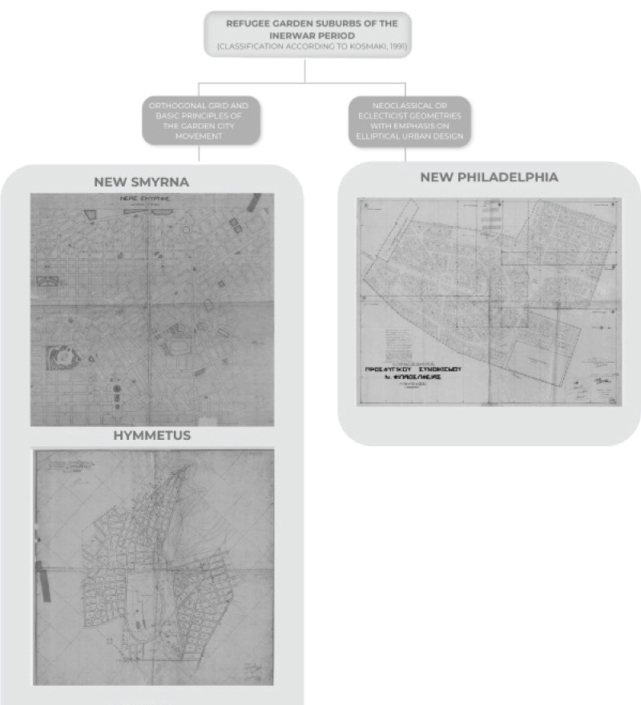

During the interwar period the first attempts to provide permanent housing to refugees had been recorded. Simultaneously, the design of the capital’s garden-suburbs had also been evolving. The Athenian garden-suburbs employed European examples as prototypes. Given this, the principles of the garden city movement influenced considerably the development of some of the urban refugee settlements of the interwar period (Κοσμάκη, 1991:247). In particular, two different planning approaches have been observed. On the one hand, many refugee settlements followed a rectangular grid, through repetition of typical forms of city blocks. In these cases, there is absence of larger scale outdoor spaces and a lack of a clearly defined settlement center. Public spaces had been limited to the inner courtyards of the city blocks and to pedestrian alleys (Κοσμάκη, 1991:288 και Ανδριώτης, 2020:36). On the other hand, the refugee garden-suburbs (N.Smyrna, Ymittos, N.Philadelphia, Elliniko) follow the basic design principles of the garden city movement, with primary and secondary, larger-scale outdoor spaces, where the center of the settlement is distinguished and well-defined (Figure 4). In both cases, the refugee settlements had not been planned as a direct continuation of the existing urban fabric (Κοσμάκη, 1991:258). In some cases, the availability of land as well as the ease of expropriation and completion of the project, played a key role in decision making (Ανδριώτης, 2020:236). Relevant sources point out that, by way of derogation from Article 19 of the Greek Constitution, land has been expropriated without any prior advance payment (Βασιλειάδης, 1944:71). It should be noted, though, that the distance (1-4 km) of the refugee settlements from the existing urban centers was a conscious choice, as a form of deliberate social and geographical exclusion (Λεοντίδου, 2017).

Figure 4: Refugee garden suburbs, based on the classification by Kosmaki (1991)

Source: Cartographic material from the Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region. Study of archival material, information synthesis, and table design by E. Tousi, 2024

Both the Refugee Relief Fund (1923-1925) and the Refugee Rehabilitation Commission (UNHCR) (1925-1930) built a significant number of refugee houses in the area of Athens (Ρούσση, 2011:148). The latest report of the Refugee Rehabilitation Commission, states that 16,345 families had been housed in the area of Athens-Piraeus and still remained 22,492 facilities to accommodate (Κοσμάκη, 1991:329). According to sources, during the period 1924-1930 a total of 15,000 refugee residences were built in the area of Athens-Piraeus (Ίδρυμα της Βουλής των Ελλήνων, 2006:52-53). After the year 1930, the Ministry of Welfare built refugee apartment complexes at Alexandras Avenue (228 apartments), at Stegi Patridos (120 apartments) and at Dourgouti (237 apartments) (Ρούσση, 2011:148).

After the interwar period, the refugee housing rehabilitation continued until the 1980s (figure 5). After World War II, relevant legislation was amended and supplemented. Moreover, a new census of households residing in slums was conducted and the Special Department for Housing Shacks was established at the Ministry of Social Welfare (Ανδριώτης, 2020:250). The signing of the “Code of Rehabilitation for Urban Refugees“, enacted on 23.5.1960, formed the framework of refugee rehabilitation in the post-war era. Article 1 describes the concept of ‘urban rehabilitation’ [3], while Article 7 mentions the demolition of shacks. These policies were associated with efforts to alter the social fabric of the refugee neighborhoods [4]. As stated by Menelaos Charalambidis (Χαραλαμπίδης, 2024:392) the settlements of the Asia Minor refugees, contributed to the development of the Resistance in the Athens region after WWII. Taking into account all the previously mentioned and with the view to contribute to the preservation of collective memory, this paper documents briefly the demolished refugee settlements, after studying archival material from the General Archives of the State and the Department of Social Welfare. These settlements were demolished [5], in various periods, independently or in successive phases, and are being presented in figure 6. Most of these accommodations consisted of a single-room-residence and a small kitchen (Τσίχλα-Μαρκοπούλου, 1996:35).

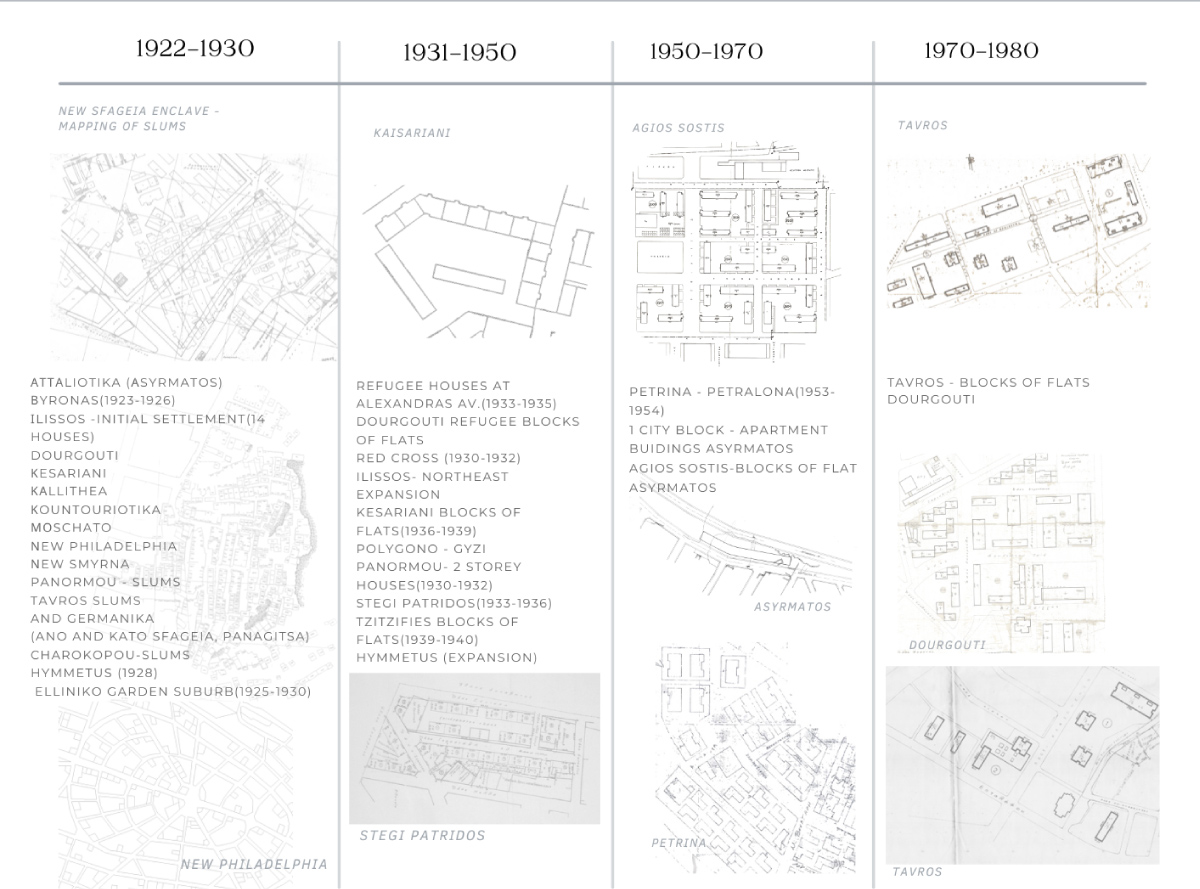

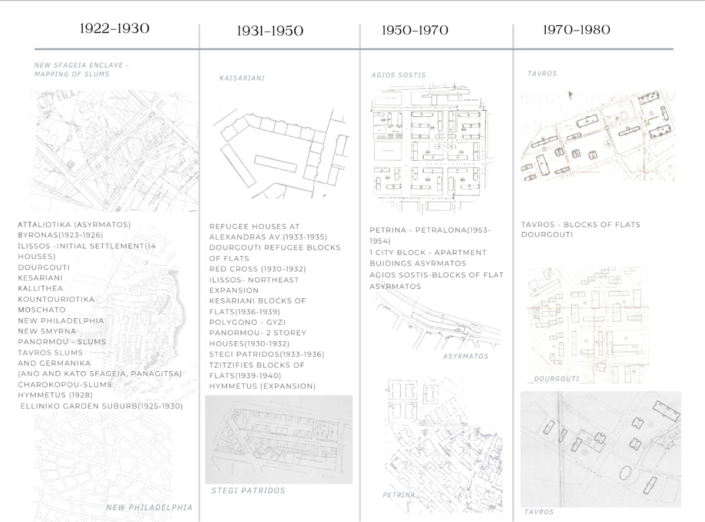

Figure 5: Timeline of refugee settlements

Source: Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region. Study of archival material, information synthesis, and table design by E. Tousi, 2024

Table 6: Demolished refugee facilities in central and southern Athens sector, authors’ work , Social Welfare Services Attica and related literature listed in the table.

Source: Archival material from a relevant table by the Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region. Study of archival material, coding, and table design by E. Tousi, 2024.

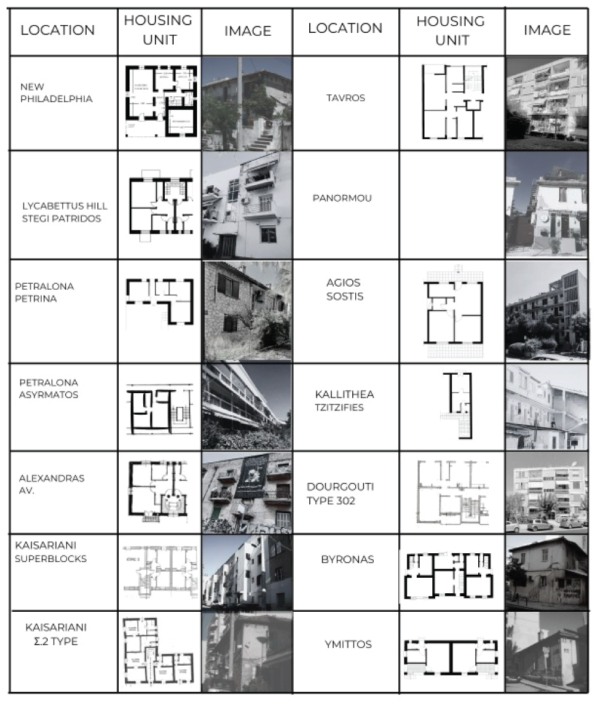

Delving into the architectural types of the urban refugee settlements in the central and southern sectors of Athens

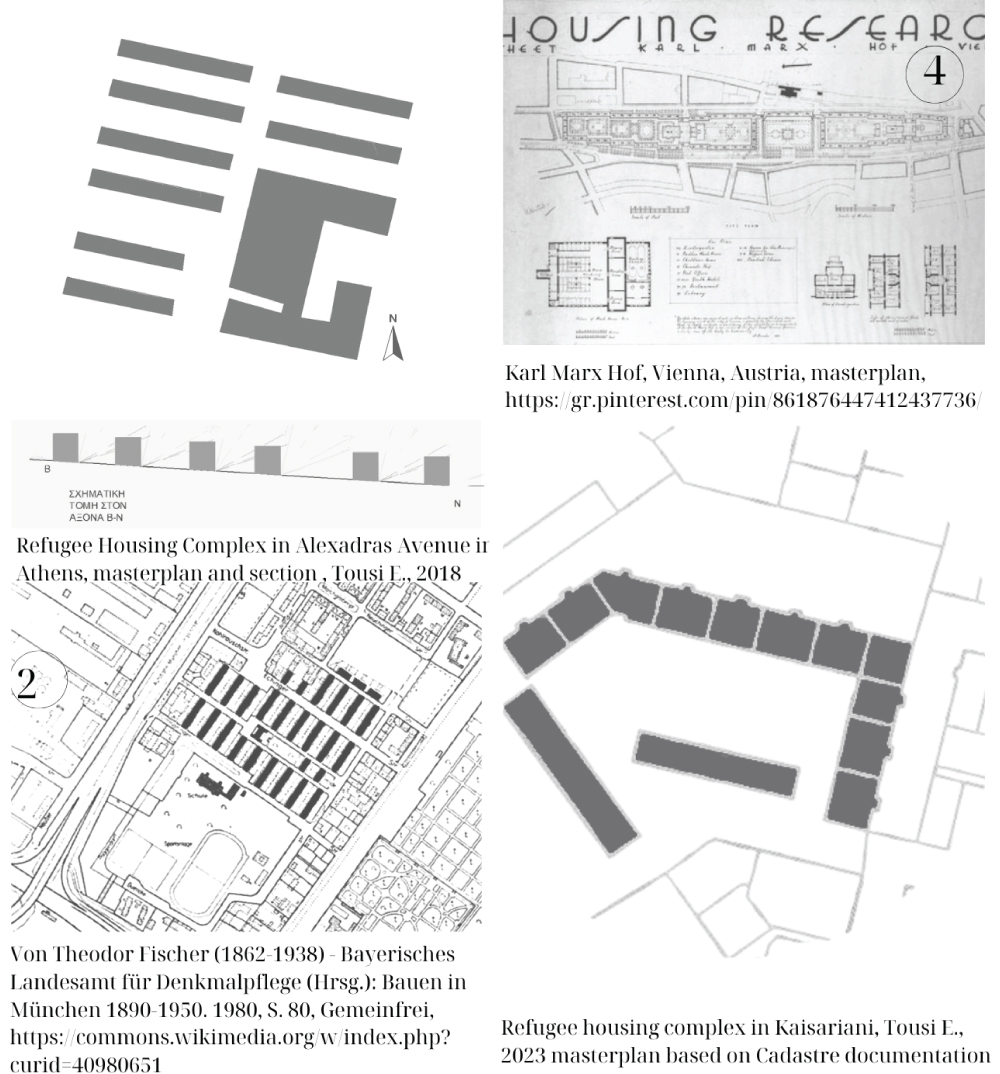

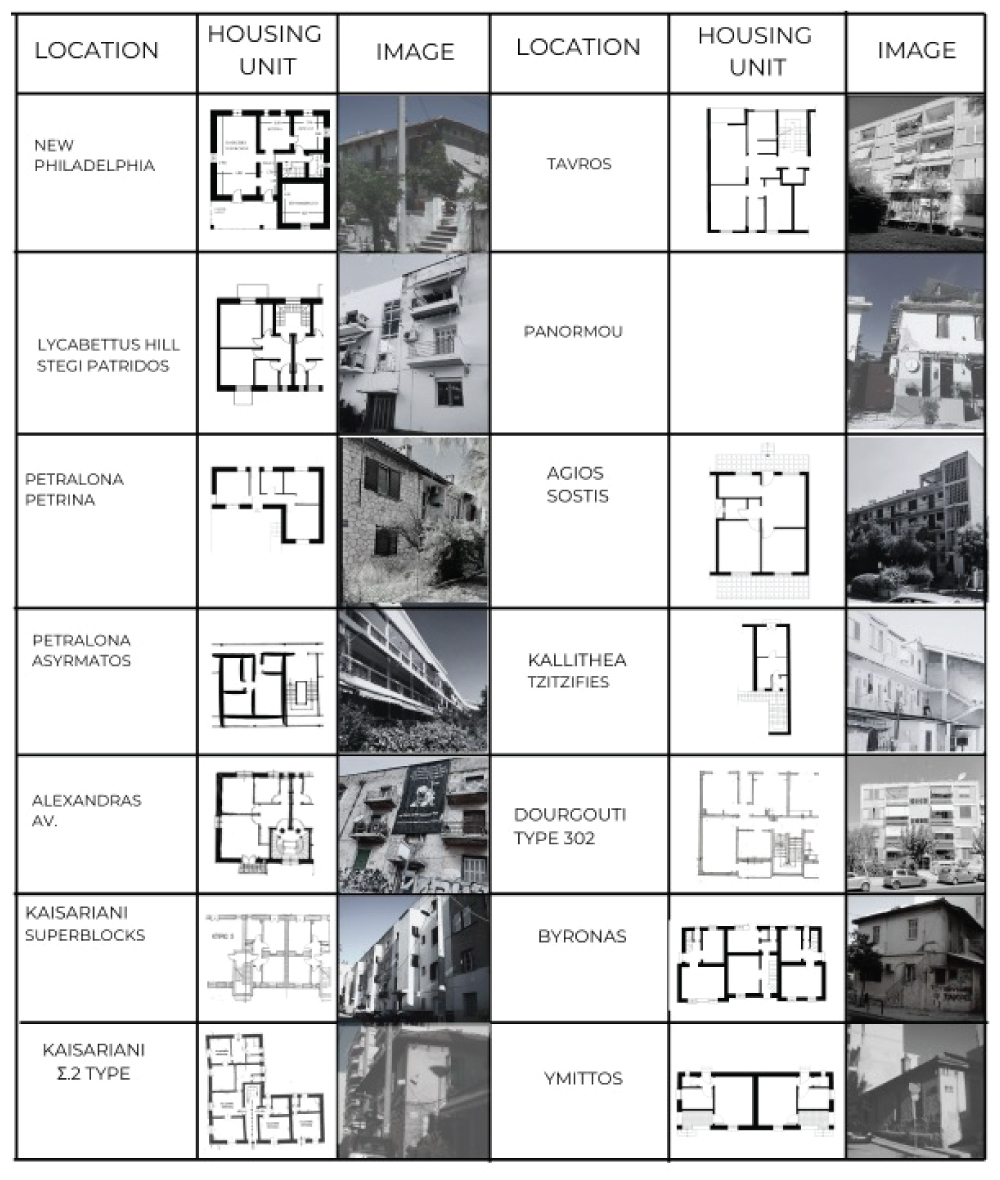

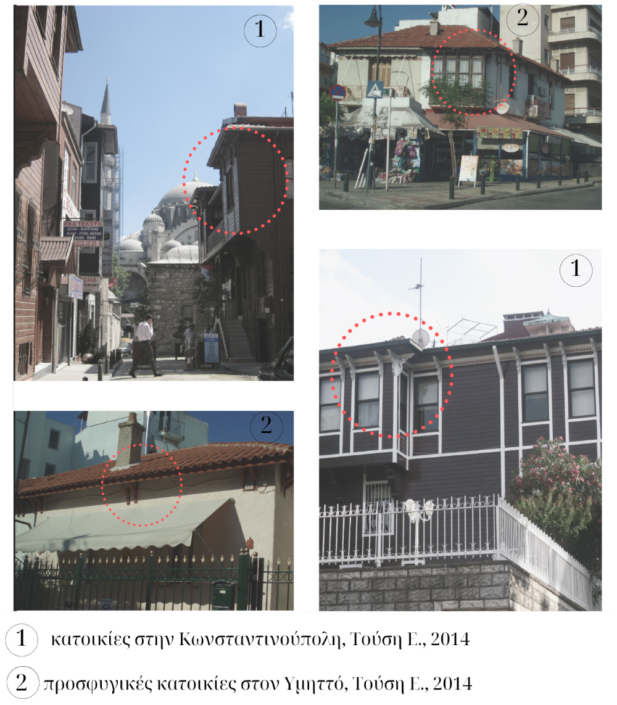

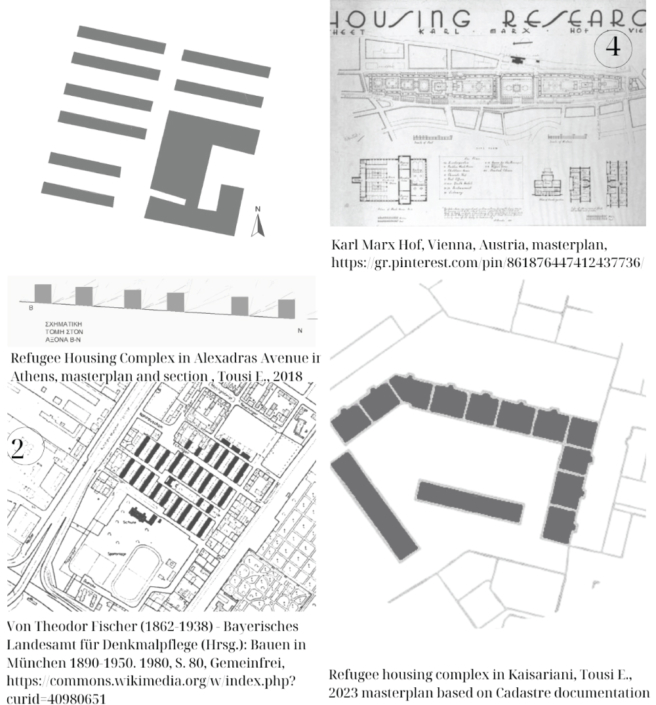

Covering a wide range of architectural and urban planning options, urban refugee settlements follow a variety of standards. The prevalent options revolve around the garden city movement, the Viennese superblocks (e.g. Kesariani), the German Zeilenbau (e.g. Alexandra) and typical forms of Hippodamian grid. However, the scale is different, with the Greek examples being distinctly smaller, compared to the corresponding European ones (Figure 7). There is also the unique case of the apartment building of Asyrmatos (1967, see Figure 5), which uses strategies such as “streets in the sky” [6] to promote social interaction among its tenants, following similar examples from the international experience (Feliz-Ricoy, 2017:526 και Borges et.al, 2019:2). These facilities range from the scale of a few city blocks (e.g. Stegi Patridos) up to the scale of a municipality (e.g. Kesariani) and are scattered within the area of today’s Central and Southern Athens Sector. Focusing on the architectural morphology, the buildings of the first period derive elements from vernacular architecture, with references to the architecture of the Ottoman period, being either ground-floor or single-floor, including one to four housing units (Figure 7), The most recent examples follow the principles of Modernism (Figures 8 & 9). Construction materials also vary: from load-bearing masonry and combination of reinforced-concrete slabs and masonry walls to structural bodies entirely from reinforced concrete. The common feature of all housing types is the small area of each apartment, with the most recent examples providing larger spaces within the house.

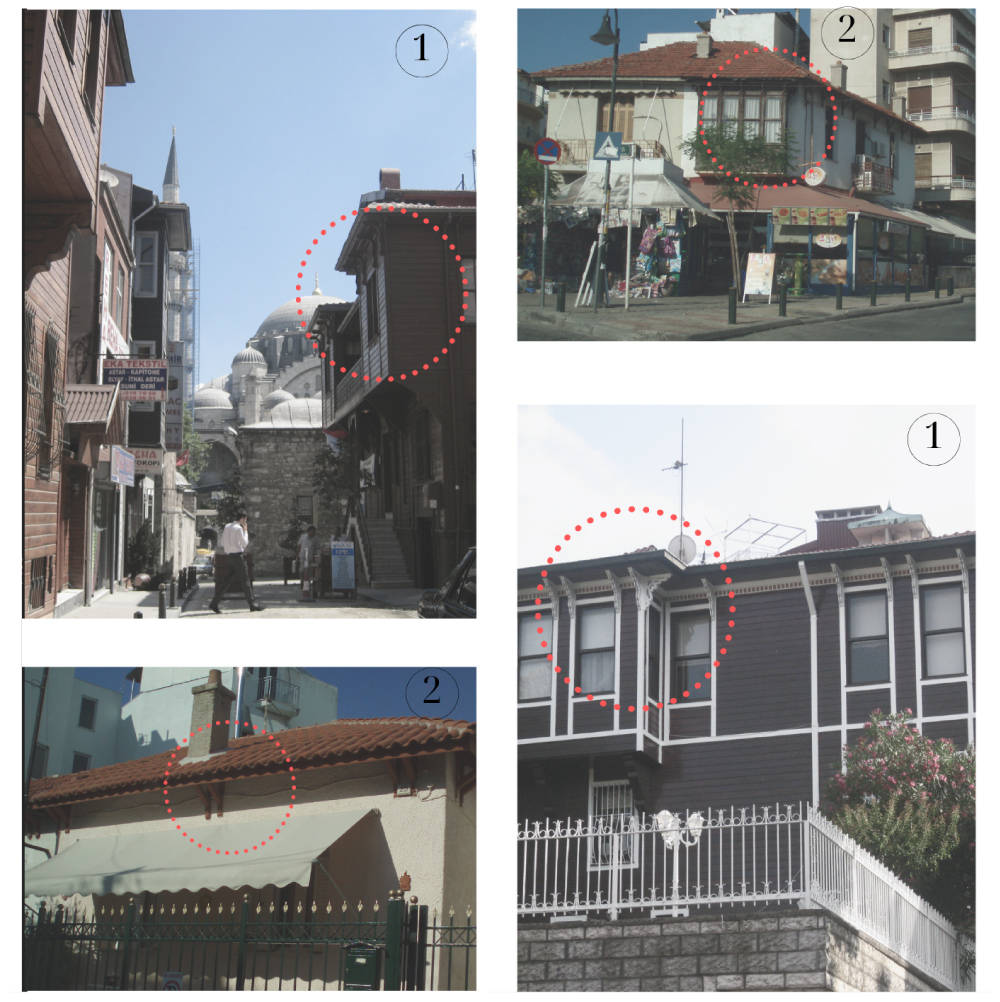

Figure 7: Residences in Istanbul (1) and residences in Hymettus (2), twin corbels, and other architectural morphological features.

Source: Source: photographic material from filed work, research by E. Tousi and material synthesis by E. Tousi.

Figure 8: General layout of the Zeilenbau example in Germany and the case of the refugee housing on Alexandras Avenue, the famous Karl Marx Hof complex in Vienna, and an example of refugee housing in Kaisariani

Source: the general topographic map of the refugee housing on Alexandras Avenue and the apartment building in Kaisariani was designed based on an orthophoto map from Ktimatologio S.A. by E. Tousi. The sources for the individual images are listed in the legend of Figure 8, and the material synthesis was conducted by E. Tousi.

Figure 9: Basic architectural types of refugee settlements in the Central and Southern Sectors of Athens

Source: Designed by E. Tousi, 2023-2024 [7]

Current Situation

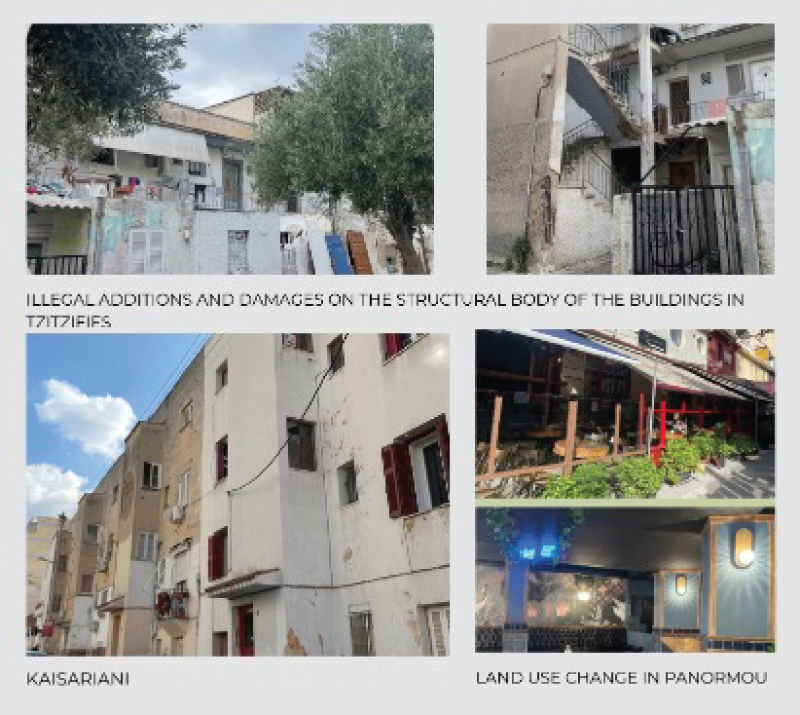

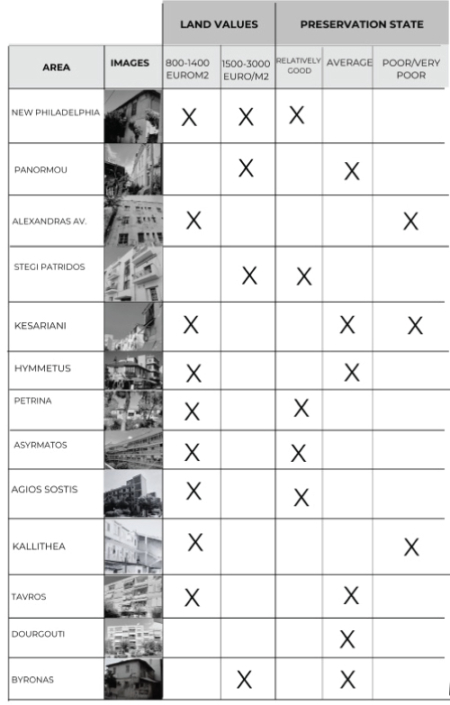

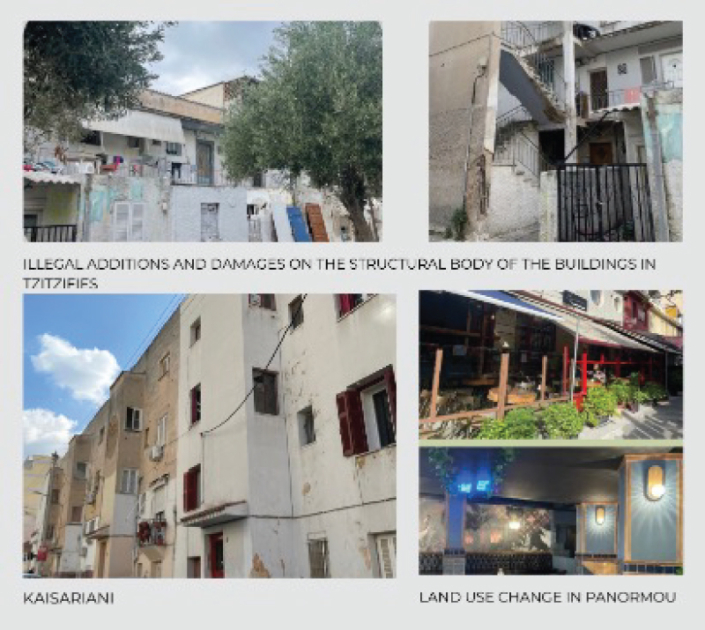

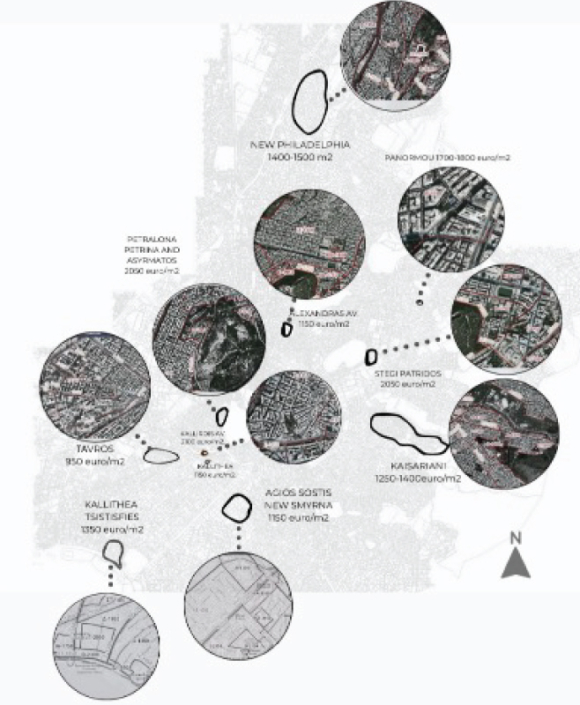

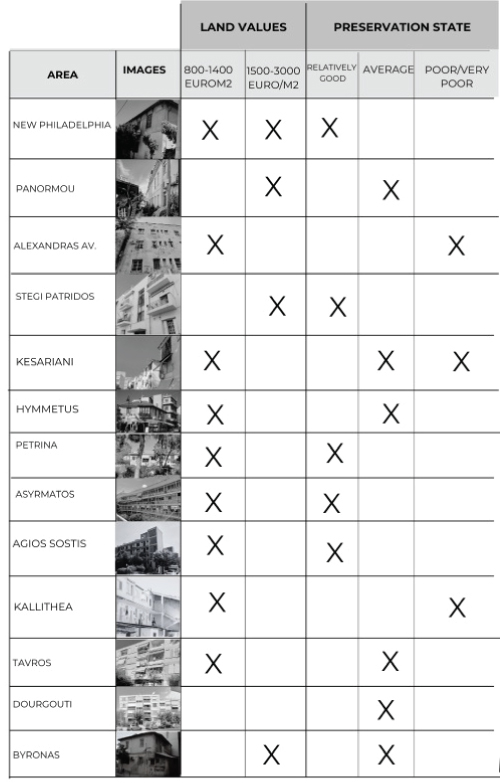

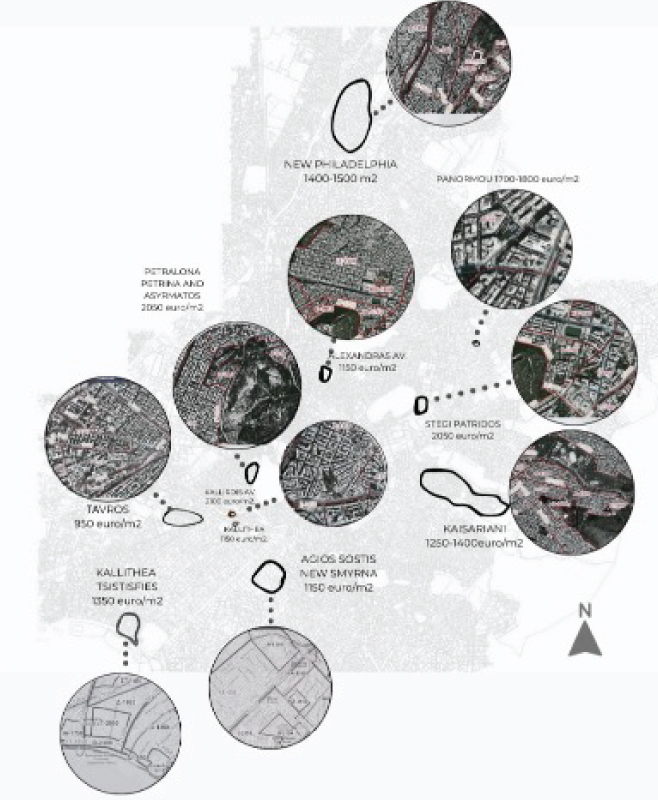

A visit to the abovementioned areas designates differences in the conservation status of the refugee buildings, the prevailing uses and the quality of surrounding public spaces. At the same time, some of the refugee enclaves still have distinct boundaries (e.g. Kaisariani, Homeland Shelter, Alexandra, Tavros etc.), while in other cases the refugee residences are found scattered within the contemporary urban fabric (e.g. Vyronas, Ymittos). In some cases, the good state of preservation is associated with land use changes, from residential uses to recreational uses (bars, cafeterias, restaurants), as observed in Kesariani Square, Panormou and to a lesser extent on Kalliroi avenue. The land and real estate values in these areas vary also widely (Figures 10 & 11). The ownership status of the refugee houses/apartments is a critical factor for the maintenance of these buildings. In many cases, the existence of multiple heirs in a refugee apartment complicates conservation and restoration procedures. According to field work, the most significant damages and the majority of empty apartments were found in Tzitzifies, in Alexandras avenue, in the large apartment buildings of Kesariani and in Kallithea (Iordani Papadopoulos street). Evident signs of deterioration are associated with damages to window frames and doors as well as coatings and, in some cases, damages to the load-bearing body of the building. Another important feature relates to illegal additions to the apartments (Figure 11). An overall assessment of the quality of the refugee’s housing stock in the study area is shown in Figures 10,11 and 12, highlighting critical enclaves characterized by low land values and severe damages to the housing stock.

Figure 10: Comprehensive assessment, zone prices, and maintenance status of refugee buildings in the study area

Source: Field research. The material was coded and the table designed by E. Tousi, 2024

Figure 11: Today’s condition

Source: Field research in Tzitzifies, Panormou, and Kaisariani. Material synthesis and design by E. Tousi, 2024.

Figure 12: Zone prices in the study areas

Figure 12: Zone prices in the study areas Source: Utilizing data from https://maps.gsis.gr/valuemaps/. A background map was used in AutoCAD by the Laboratory of Spatial Planning and Geographic Information Systems, Sector II of Urban Planning and Spatial Planning, School of Architecture, NTUA (2013). Material synthesis and map design by E. Tousi, 2024.

Source: Utilizing data from https://maps.gsis.gr/valuemaps/. A background map was used in AutoCAD by the Laboratory of Spatial Planning and Geographic Information Systems, Sector II of Urban Planning and Spatial Planning, School of Architecture, NTUA (2013). Material synthesis and map design by E. Tousi, 2024.

It is important to mention that the majority of the examined areas are not under an architectural preservation regime. In particular, the Modernist housing complex of Alexandras Avenue and a refugee complex in Kallithea have been declared as listed monuments by the Ministry of Culture. In addition, the refugee’s suburb of Nea Philadelphia has been declared a protected traditional settlement (Law ΦΕΚ 476D). There are also a few scattered refugee houses declared by the Ministry of Energy and Climate Change in Kesariani. As has already been stated by researchers (Παπαδοπούλου και Σαρηγιάννης, 2006:9) the effort to declare refugee complexes as architectural monuments is a highly complex process, which involves socio-economic aspects in decision making.

Conlusions

The article presents an overview of the current situation of the refugee houses/complexes of the central and southern Athens’s sector, presenting also their initial planning framework. Combining literature review and fieldwork, the study concludes to the fact that initial architectural design plays a key role in the current state of preservation. In view of this thesis the small apartments of approximately 35m2, organized in large-scale residential complexes, failed to meet contemporary housing needs and are now mostly abandoned. Moreover, the small area of the apartments led to illegal additions to the building and on the surrounding outdoor spaces. On the other hand, smaller scale apartment buildings with larger housing units are found in better state of preservation. In addition, new uses have facilitated the active integration of former refugee houses into the contemporary urban fabric. The fact that the majority of the refugee housing stock is not under an architectural preservation regime, raises concerns about the future of these buildings and thus about the maintenance of the urban collective memory.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to warmly thank Ms. Penny Kampaki, Architect Engineer NTUA, Dr. Vasso Roussi, Architect Engineer NTUA, Mr. Thomaidis and Ms. Giannaki from the Department of Social Welfare, Region of Attica, as well as DIKEMES/College Year in Athens for supporting the field research, and the residents of the areas who participated in the study. They would also like to thank Ms. Kate Donnelly for the initial language editing of the English text.

[1] In 1982, the Oxford University Refugee Curriculum was established and in 1988, the Journal of Refugee Studies.

[2] Gizeli (1984, 10) mentions 1 500 000 and the League of Nations (1926) “The settlement of refugees in Greece” refers to 1 400 000 refugees, clarifying that the number is not accurate because many refugees, for various reasons, were not recorded on arrival in Greece.

[3]Text of the Article, Chapter I, Beneficiaries-Conditions-Award procedure (Art. 1 of 27-1/9.2.1953 (B.D.)

[4]See Sarigiannis, “The historical context: The political situation after 1949 (end of the Civil War)

[5]Information on this subject is also provided in Papadopoulou and Sarigiannis, 2006 (Παπαδοπούλου και Σαρηγιάννης,2006)

[6]The “streets in the sky” in social housing include elevated corridors connecting residential buildings or parts of the same building, creating routes above ground level. Representative examples include the Park Hill Estate in Sheffield and the Robin Hood Gardens in Londο.

[7] The photographic material is original and was collected during the field research conducted by the authors, in the winter semester of the academic year 2023-2024 durng the course “Sustainable Social Housing,” CYA, Fall semester 2023-2024. The floor plans of Agios Sostis and Nea Filadelfia are products of E. Tousi’s documentation as part of her doctoral dissertation (Tousi, 2014). The floor plan of the Petrina was provided by fellow architect Penny Kampaki. For the floor plan of the refugee housing on Alexandras Avenue, material was sourced from the website https://archaeologia.eie.gr/archaeologia/gr/arxeio_more.aspx?id=1, For the design of the floor plan in Tzitzifies, material was sourced from Vasileiou, 1944, under the guidance of Dr. Vasso Roussi. For the floor plan in Vyronas, material was sourced from the Hellenic Parliament Foundation, 2006, p. 53. All other floor plans were sourced from archival material of the Department of Social Welfare, Attica Region, and the General State Archives. The floor plans were designed in AutoCAD and edited in Photoshop by E. Tousi, 2024

Entry citation

Τousi, Ε., Cavanaugh, A., Conte, I. K., Erickson, A., Hill, J. E., Hochman, A.Ga., Iannios, M., McCracken, F.R., Schwab, J., Skylar, Y. (2024) Current state of building stock in the refugee settlements of the Central and Southern Sector of Athens, in Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/en/article/the-refugee-settlements-of-athens/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.126

Atlas citation

Maloutas T., Spyrellis S. (eds) (2015) Athens Social Atlas. Digital compendium of texts and visual material. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.9

Références

- Ανδριώτης Ν. (2024) Πρόσφυγες στην Ελλάδα 1821-1940, Άφιξη, Περίθαλψη, Αποκατάσταση, Ίδρυμα της Βουλής των Ελλήνων, Αθήνα

- Βασιλείου Ι. (1944) Η Λαϊκή Κατοικία, Κοινωνικές Τεχνικές και Οικονομικές Απόψεις,Η Λαϊκή Κατοικία σε διάφορες ξένες χώρες και στην Ελλάδα, Αθήνα

- Βεϊνογλου Φ. και Μ. (1997) Κοινωνία των Εθνών, Η εγκατάσταση των προσφύγων στην Ελλάδα, Γενεύη 1926, Εκδόσεις Τροχαλία, Αθήνα

- Γκιζελή Β. (1984) Κοινωνικοί Μετασχηματισμοί και προέλευση της Κοινωνικής Κατοικίας στην Ελλάδα (1920-1930), Εκδόσεις Επικαιρότητα, Αθήνα

- Clark B. (2009) Twice a Stranger: The Mass Expulsions that Forged Modern Greece and Turkey, Harvard University Press

- Chimni B.S. (2009) «The birth of a ‘discipline’: From refugee to forced migration studies», Journal of Refugee Studies, τόμ. 22, τχ. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, DOI:10.1093/jrs/fen051

- Cunha Borges, Joao & Marat-Mendes, Teresa. (2019). Walking on streets-in-the-sky: structures for democratic cities. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture. 11. 1596520. 10.1080/20004214.2019.1596520., https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333212330_Walking_on_streets-in-the-sky_structures_for_democratic_cities

- Ελληνική Στατιστική Αρχή (2022) Απογραφή Προσφύγων 1923, διαθέσιμο στο https://www.statistics.gr/elstat-apografi_prosfyges_1923

- Feliz-Ricoy S. (2017) EXTRA-LONG RESIDENTIAL INFRASTRUCTURES. THE OUTDATED PROGRAMME IN THE COLLECTIVE HOUSING ON THE LARGE-SCALE at Living and Sustainability: An Environmental Critique of Design and Building Practices, Locally and Globally, AMPS, Architecture_MPS; London South Bank University, 09—10 February, 2017

- Ίδρυμα της Βουλής των Ελλήνων (2006) Η Αττική γη υποδέχεται τους πρόσφυγες του ’22, Κατάλογος έκθεσης, Αθήνα

- Κοσμάκη Π. (1991) Σχεδιασμένοι οικισμοί στην Αθήνα του Μεσοπολέμου, Πρότυπα, Εξέλιξη και επιδράσεις στο μεταβαλλόμενο αστικό χώρο, Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών ΕΜΠ

- Λεοντίδου, Λ. (2017) Φτωχογειτονιές της ελπίδας, στο Μαλούτας Θ., Σπυρέλλης Σ. (επιμ.) Κοινωνικός άτλαντας της Αθήνας. Ηλεκτρονική συλλογή κειμένων και εποπτικού υλικού. URL: https://www.athenssocialatlas.gr/άρθρο/φτωχογειτονιές-της-ελπίδας/ , DOI: 10.17902/20971.70

- Παπαευαγγέλου-Γκενάκου Κ. (2023) Το παλίμψηστο της Αθήνας, Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος, Αθήνα

- Παπαδοπούλου Ε. και Σαρηγιάννης Γ.(2006) Συνοπτική Έκθεση για τις προσφυγικές περιοχές του λεκανοπεδίου Αθηνών, Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών, Τομέας Πολεοδομίας – Χωροταξίας ΕΜΠ, Σπουδαστήριο Πολεοδομικών Ερευνών

- Ρούσση Β. (2011) Τα σπίτια του Μεσοπολέμου στην Αττική. Αστική, προαστική, εξοχική κατοικία., Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών ΕΜΠ

- Σαρηγιάννης Γ.Μ. (2000) Αθήνα:1832-2000 [Athens 1832-2000], Εκδόσεις, Συμμετρία, Αθήνα

- Τζεδόπουλος Γ. (2007) Πέρα από την Καταστροφή, Μικρασιάτες Πρόσφυγες στην Ελλάδα του Μεσοπολέμου, Ίδρυμα Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Αθήνα

- The National Geographic Magazine (1925) «Η μεγαλύτερη μετακίνηση πληθυσμών στην ιστορία», (Νοέμβριος 1925, ελλ.εκδ.Αθήνα, 38-41, αναφέρεται στο Ανδριώτης Ν. (2020) «Πρόσφυγες στην Ελλάδα 1821-1940. Αφιξη, Περίθαλψη, Αποκατάσταση» Ιδρυμα της Βουλής των Ελλήνων, Αθήνα

- Τούση Ε. (2014) Ο αστικός χώρος ως πεδίο μετασχηματισμών υπό το πρίσμα του προσφυγικού ζητήματος. Η περίπτωση της ευρύτερη περιοχής Αθήνας Πειραιά. [Urban socio-spatial transformations in the light of the refugee issue. The case of the urban agglomeration of Athens-Piraeus.] Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Εθνικό Μετσόβειο Πολυτεχνείο, Σχολή Αρχιτεκτόνων Μηχανικών, Τομέας Πολεοδομίας και Χωροταξίας διαθέσιμο στο https://thesis.ekt.gr/thesisBookReader/id/42796#page/1/mode/2up

- Χαραλαμπίδης Μ. (2024) Οι Δωσίλογοι, Ένοπλοι, πολιτική και οικονομική συνεργασία στα χρόνια της Κατοχής, Εκδόσεις Αλεξάνδρεια, Αθήνα

- Χίρσον Ρ. (2004) Κληρονόμοι της Μικρασιατικής Καταστροφής, Μορφωτικό Ίδρυμα Εθνικής Τραπέζης, Αθήνα